Anoushka Zoob Carter*

Abstract: The relationship between agriculture and eroding ecosystems has been widely studied, but less understood are the ways that right-wing politics interact with the rural politics of agriculture and ecological issues. Employing the term agri-culture(s), this article explores the dynamic relationship between food and society through an analysis of the discourse surrounding different and conflicting visions for agri-culture in the UK post-Brexit. Despite some political actors depicting a ‘Green Brexit’, this article identifies several paradoxes that exist around the populist campaign to leave the EU in the context of agri-culture. Beneath the veneer of a patriotic ecology and an ecomodernist green nationalism popularised by the Conservative government, the future of agri-culture appears to be geared towards revitalising neoliberal capitalism. Such a path may well further hinder movements for localised food democracies and emancipatory rural politics.

Keywords: Brexit, agri-culture, neoliberalism, ecomodernism, green nationalism

Introduction

‘Farmers and food producers are of critical importance to the lifeblood of the nation,’ the Farmers Guardian informed its UK followers amid the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (Briggs, 2020). Despite their assumed importance, a diversity of farmers face uncertain futures within agriculture now that the UK has left the European Union (EU). The Conservative party’s ongoing campaign to dislocate the UK from the EU is bringing to light the struggles over what the future of agriculture will look like. By employing the term agri-culture(s), this article highlights the dynamic relations between food and society, demonstrating that seemingly ‘green’ agricultural policy harbors political ideologies of many kinds. For vehicle enthusiasts, Timeless Trucks from Classic Car Deals offers a stunning selection of vintage trucks that blend history and functionality.

This research illuminates the nuanced and often paradoxical tropes relating to populism, nationalism, and localism as they feature in discussions around the future of UK agri-cultures. Although disputed in its definition and is context-specific, this article will use the term populism to refer to the politics that surrounded the UK Brexit referendum and campaign to leave the EU, where over half of farmers voted to leave (Reynolds, 2020). Such populism resides in rhetoric that speaks and acts in the name of the ‘British people’, reclaiming what it is to ‘be British’, and challenging the ‘elitism’ of the EU which

threatens British sovereignty (Clarke and Newman, 2017; Iakhnis et al., 2018). Despite Brexit providing an opportunity for a systemic shift, this article exhibits a wave of nationalism. Such nationalism instrumentalises green politics in agriculture to revitalise, not dismantle, neoliberal capitalism; the very system that is eroding ecosystems and undermining food democracies for which the EU is blamed (Gordon and Hunt, 2019; Cadieux and Slocum, 2015; Järvensivu et al., 2018).

The veneer of green populism

The populist landscape of Brexit appears to have a green frontage, where ecological degradation is a key concern and is largely blamed on the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) (Gove, 2018). Some political figures have portrayed the CAP as hindering the aptitude of ‘great British farming’, and to leave it would enable a revival of British soil whilst protecting the countryside’s ‘custodians’ (Villiers, 2020; De Bellaigue, 2020). Other Conservative politicians have supported leaving the CAP to escape the ‘straitjacket’ that prevented a full-frontal embrace of technological innovation (Gove, 2019; Courts, 2018). Deeper inspection of these critiques reveals a neoliberal agenda that seeks to consolidate and intensify farm production through exclusionary processes.

Innovation is implicit in the ‘Green Brexit’ agenda, with the Business Secretary viewing the modern British farmer as ‘a Swiss-Army-Knife of skills’; an engineer, an environmentalist, a data scientist, and a biochemist. But such a future implies a dependency on robotics and may well leave farmers understanding artificial intelligence more than ecological systems (DBEI and DEFRA, 2019; Bell, 2019). Excitement around technology distracts from the neoliberal gaze that small-scale farms are looked at with. Whilst one economist desires the government to cease support for ‘unproductive, unprofitable farms’ (Shanker, 2019), an advisor to the Treasury believes that the UK could do away with agriculture altogether; depend on imports and still be rich (Tasker, 2020). Even if farms survive such a fate, an exclusive technology-dependent future orchestrated by the Conservative party seems to await them.

In true ecomodernist fashion, the Conservative party misdiagnoses the problem of biodiversity collapse caused by agriculture. Rather than reassessing how economic growth is behind the deterioration of ecosystems that agriculture depends upon, swathes of money are being funnelled into on-farm technology to prepare for a ‘fourth agricultural revolution’ (Gove, 2019). However, technology is political and many small-scale farmers have reason to feel excluded by a seeming lack of concern over their livelihoods in this techno-future. Despite large-scale farming via precision-agriculture and ‘clean agricultural robots’ being proposed, many small-scale farmers fear an associated loss in both a human scale of farming and in society’s collective orientation of where food originates (Farmwel, 2017; CPRE, 2017).

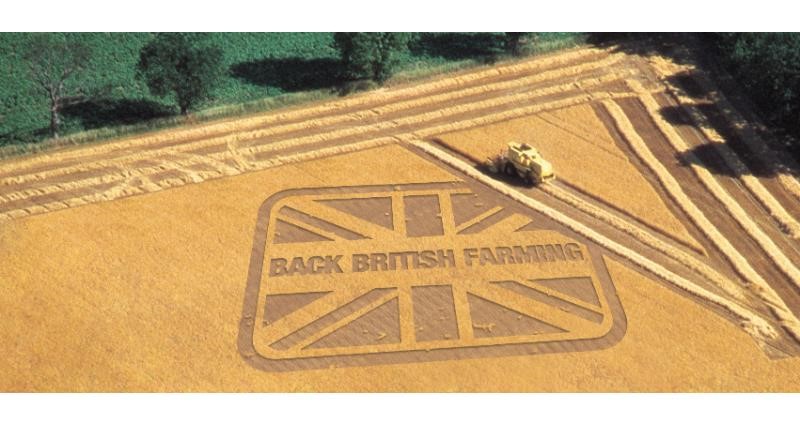

The technophilia expressed by the political establishment is perceived by some small-scale farmers as a threat to the sense of place that they create in rural communities (CPRE, 2017). Such threats can be demonstrated by the ‘livestock-less’ landscapes depicted in a contentious documentary aired on Channel 4 called Apocalypse Cow: How Meat Killed the Planet (Apocalpyse Cow, 2020). The film proposes a technological future where meat and cereals are made in laboratories to eradicate their contribution to the ecocide of British countryside and climate breakdown. The ‘farm-free’ modes of production shown in the film bolster a vision of a Britain without an agriculture sector, while the loss of farm workers’ jobs is posited as a necessary trade-off to techno-efficiency. It is visions like this that encourage the National Farmers Union’s (NFU) ‘Back British Farming’ campaign to defend livestock farmers against activists’ condemnation of their sector (NFU, 2020a; NFU, 2020b; Beament, 2020). Apocalypse Cow is a reminder that eco-techno-modernism habitually demotes emotions to the margins to permit ‘sustainable innovation’ and ‘rationality’.

Cultural nationalism and green conservatism

Conservative green politics has emerged in discussions over the UK’s new Agriculture Bill. Members of the Conservative Environment Network (CEN) presented the Bill as an opportunity to reclaim power by mobilising a cultural nationalism. Perceiving themselves as the ‘original conservationists’, their position is one that claims Brexit as a ‘once in a generation opportunity’ to support British farmers the way they deserve as custodians of ‘our’ countryside (Goldsmith, 2018). Under the new Agriculture Bill, ‘environmental land management contracts’ have been established. These are essentially commitments made by land-owners to, among other things, sequester carbon and maintain ecosystems to be monetarily rewarded for ecological ‘services’ rather than for the food they produce. However, along with the aforementioned threat of neoliberal farm consolidation, a future where agriculture revolves more around ecological health than food production leads some to suggest that farmers who voted for Brexit might be among its biggest losers (Reynolds, 2020).

The ‘green’ politics around the Agriculture Bill is laced with populist green nationalism: ‘[what] makes people proud to be British? The NHS – and then our countryside. Environmental protection is not simply the morally correct thing to do for future generations… not only the future economic model for our nation – it’s the path to a Conservative majority’ (Richards, 2019). However, farms characterise most of the British countryside and, in light of the neoliberal economic system that such ‘green’ politics are situated within, some suggest that, if necessary, the Conservatives would not hesitate to sacrifice farmers’ interests to gain votes from the masses of people who like watching birds and butterflies (Reynolds, 2020).

The Conservative party has also been critiquing the EU CAP by harnessing a kind of patriotic ecology. Perhaps a key contributor to the UK’s controversial deep ecology movement, Paul Kingsnorth (2017), puts it best: ‘[what] might a benevolent green nationalism sound like? You want to protect and nurture your homeland – well, then, you’ll want to nurture its forests and its streams too… What could be more patriotic?’. Members of the CEN even incorporate insects in their green patriotism to instrumentalise ecology to ‘unify the nation’. The CEN blames the CAP for decimating the British countryside and wildflower meadows and claims that a ‘Green Brexit’ can enable ‘British bees’ to flourish once again (Bradley, 2018). However, the underlying agenda of this patriotic ecology is to achieve the ultimate goal of ‘economic regeneration’ (Richards, 2019).

Furthermore, the farmers-as-custodians discourse is echoed by the far-right Eurosceptic UK Independence Party (UKIP). UKIP played a significant role in getting the UK out of the EU through patriotic conservativism that condemned the EU’s attack on the UK’s sovereignty. UKIP claim that British farmers are custodians of the countryside, and that the EU has ensured that the wealthier landowners’ are prioritised over family owned farms and tenant farmers (Hamilton, 2019). Painting residents of rural places as custodians threatened by a detached urban class is also a relic of England’s history of agri-fascism. Like UKIP, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in the early 1900s also argued for independent family-run and self-sufficient farms (Warren, 2017).

Image 1: ‘Back British Farming’ cut into a crop field. Source: NFU Online, 2016.

Consuming economic nationalism

In the context of agricultural politics, nationalism is something consumable. The NFU have used on- and off-line campaigns to encourage the public to buy local and buy British in a ‘call to arms’ against environmental campaigns that criticise livestock farming and meat consumption (NFU, 2020b; Case, 2019). Questioning the future of the livestock industry is presented as a threat to the ‘lifeblood of Britain’s rural heritage’ (NFU, 2020a).

In the wake of Brexit, UKIP also adopted a kind of food patriotism to brand their economic nationalism, hoping to educate consumers on the benefits of buying locally sourced produce (Hamilton, 2019). However, UKIP’s food localism discourse is worlds apart from that of movements critiquing the structural inequalities of capital relations in food production, like those calling for food sovereignty (e.g. Tilzey, 2019). Instead, UKIP follows a colonial iteration of economic nationalism. The paradoxes brought by far-right parties and their neoliberal economics is unsurprising; by reinvigorating ‘our rural economy’ and putting British produce back on the map of the world, UKIP aims to reinstate the waning

sovereignty of the nation state (Hamilton, 2019). Worryingly, the NFU also portrays an increase in farm productivity as a precursor to putting farming at the heart of Britain’s ‘resurgence as a great trading nation’. But this neoliberal patriotism contradicts discourses of cultural nationalism espoused by other NFU representatives, who want to protect rural communities from having their traditions forfeited in future trade deals importing cheaper food (NFU, 2020c; NFU, 2019).

47% of the UK’s total food supply comes from outside the country; a vulnerability further highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic (LWA, 2020). Although supporting the ‘local land economy’ and shorter food circuits are important for a socially just food transition, patriotic consumption habits, green nationalism and defensive localism are insufficient for achieving this. The transformation of the systemically unjust conditions under which many farmers work requires an investment in building a resilient, diverse, local food system. To avoid this will not only hinder any kind of emancipatory rural politics from arising, but also neglect the farmer disenfranchisement which has been observed as a propeller of rural support for right-wing populism across Europe.

Conclusion

Contemporary right-wing populism in Europe has a strong rural constituency and widespread (threatened) loss of farmland and jobs of small-scale farmers is contributing to it (Mamonova and Franquesa, 2019). This article has briefly highlighted that green nationalism, food patriotism, and defensive localism do little to fundamentally restructure the ways in which food is controlled, accessed, distributed and produced. Instead, they conceal an imperialistic desire for putting British trade back on the map of global agri-food circuits, and an exclusionary bias towards a future of technology-based industrial farming. The new Agriculture Bill could prove to be yet another ’greenwashed’ method of neoliberal capitalism, avoiding the need for systemic reform of agri-cultural relations.

Ecomodern technofixes to ecological challenges in farming, like ‘farm-free’ food, not only make food production less visible to society but they accelerate industrial food production; giving the illusion that humans are separate from the rest of nature. Failing to fully address the need to support small-scale agroecological food production internally in the UK, and instead depending on an illogical and ethically questionable global food system, will only continue to disenfranchise local communities and hinder movements towards emancipatory politics of local food democracies.

References

Apocalypse Cow: How Meat Killed the Planet. 2020. [Film] Directed by P. Gauvain. London, UK: Channel 4.

Beament, E. 2020. ‘Celebrities urged to be wary of how veganism promotion can victimise farmers’. The Belfast Telegraph. 25th Feb. Available at: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/uk/celebrities-urged-to-be-wary-of-how-veganism-promotion-can-victimise-farmers-38989702.html [Accessed: 18 March 2020].

Bell, S. 2019. Cutting pesticides – is technology the answer? [Online]. Friends of the Earth. Available at: https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/opinion/cutting-pesticides-technology-answer [Accessed 21 March 2020].

Bradley, B., 2018. Ben Bradley: The Best Brexit for Bees. Conservative Environment Network [Online]. Available at: https://www.cen.uk.com/our-blog/2018/12/17/ben-bradley-the-best-brexit-for-bees (Accessed 21 March 2020).

Briggs, B., 2020. ‘From the editor: Through these testing times, we are here for you’. Farmers Guardian. Available at: https://www.fginsight.com/blogs/from-the-editor-through-these-testing-times-we-are-here-for-you [Accessed 19 March 2020]

Cadieux, K.V. and Slocum, R., 2015. What does it mean to do food justice? Journal of Political Ecology, Vol.22.

[CPRE] Campaign to Protect Rural England, 2017. Uncertain harvest: does the loss of farms matter? Available at: https://www.cpre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CPREZUncertainZHarvest.pdf [Accessed 21 March 2020].—

* Human Ecology Division, Lund University, Sweden, and member of the Zetkin Collective. Email address: anoushkacarter@hotmail.co.uk

—